I’d like to preface this piece by saying that my heart goes out to all affected by the recent fires. Resources for victims of the fire can be found here.

I don’t have a high school diploma, far less a P.h.D in environmental science, economics, poli-sci, or anything that might help me understand the tragedy of the Los Angeles fires on a technical level. But my feeling is that it may not be a bad thing. Maybe my lack of qualification has afforded me a view with a welcome sense of naivety; or what I feel to be “human.”

Of course, I run the risk of romanticizing my ignorance. An educated stance is a necessary part of analyzing and dissecting disasters, but perhaps empathy is the missing piece of the puzzle.

The concept of feeling “human” seems to be lost within the fires. Watching the news coverage, I couldn’t help thinking that it was masochistic, zeroing in on the absolute lowest points of people’s lives. Rather than focusing on providing resources and information about the tragedy, the narrative is being built around human-interest stories: “How do you feel about your house burning down?”

It seems insane, but parts of the coverage could easily slip into a Ruben Ostlund1 film—satirical, hyperbolic, yet way too real. It’s like modern disaster reporting has become less about informing and more about engaging in a collective schadenfreude.

This shift raises the question—are we the viewers to blame? Have we tacitly encouraged this style of reporting because we crave the emotional spectacle? Or are journalists skirting the deeper, more uncomfortable truths about disasters to shield us from the complexity of climate change, systemic inequality, and the failures of governance?

I would if human-interest stories have become a safety net for us. A way to avoid the crushing weight of the broader narrative. Climate change is terrifying, the growing income inequality feels increasingly insurmountable, and the systemic injustices that course through the country’s veins are as real as ever. Perhaps focusing on human interest stories presents us with a more digestible story, something small and manageable, to distract us from the bigger picture.

I often float from day to day begging for no new headlines highlighting a new terrorist organization or political campaign moving us away from a safer world, so I wonder if the pathos of human interest stories is what we’ve collectively decided is all we can handle, and the deeper, more complex elements are left for the individual to think about.

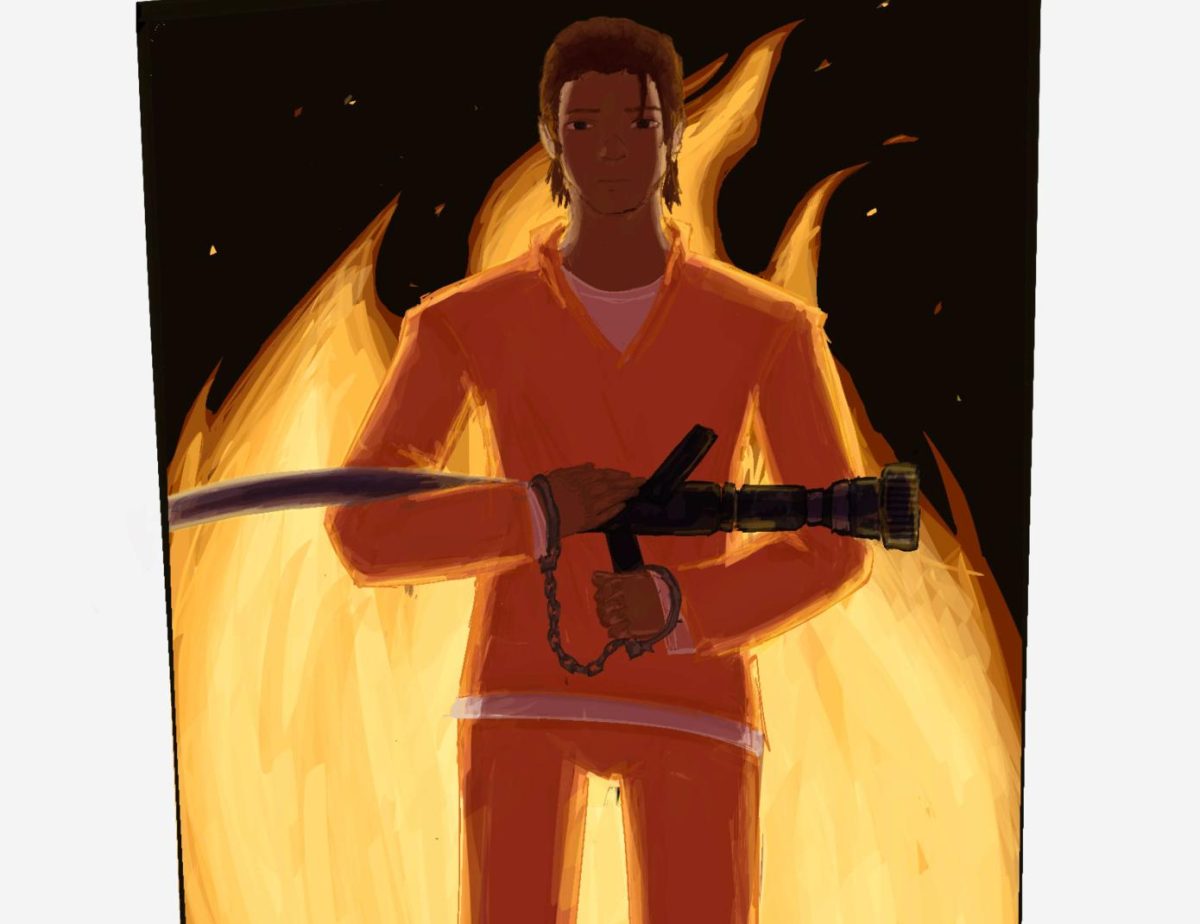

Generally speaking, when a natural disaster hits, it disproportionately affects the working class, and working class people of colour in particular. With the recent Los Angeles fires, the script has been flipped. Headlines of multi-million dollar homes in Malibu and the Palisades down are everywhere.

What frustrates me is how heavy-handed and sensationalized the news coverage is. There’s no nuance. Instead of asking why wildfires have become so catastrophic—how climate change is making them more frequent, why the growing income inequality shapes who can recover from these disasters and who can’t—we stick cameras in the face of people that just lost everything.

It’s not that personal stories don’t matter, they do. They humanize tragedy. But they can’t be the whole story. When individual stories take the center stage, it distracts from the bigger picture.

For me, the biggest question being asked during a natural disaster is this: Can a community unite in a time of tragedy, or will it crumble like we’ve seen time and time again?

We’ve seen both outcomes time and time again, and yet, this essential story—of human connection, resilience, and failure—rarely makes the headlines. Maybe it’s not dramatic enough. But it seems like the most “human” way of talking about it.