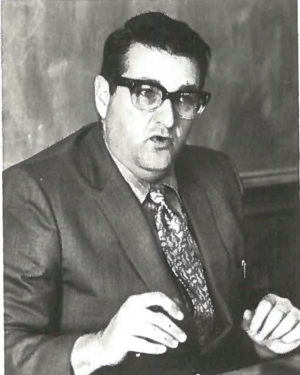

Gondolier Adviser and Venice teacher Bud Rotman has died

A.H. “Bud” Rotman, former Gondolier and Oarsman Adviser and English teacher

July 20, 2018

Longtime Venice High School English teacher and Oarsman and Gondolier advisor A.H. “Bud” Rotman has passed away in Meridian, Idaho, after a long illness. He was 90.

Rotman taught English literature, Shakespeare at Venice from 1958 to 1988, almost all in bungalow 21, which came to be regarded as a kind of student salon. For most of those years he served as advisor to The Oarsman and the VHS yearbook, The Gondolier.

“Mister Rotman” was a popular, genial, jesting presence on campus, down-to-earth in manner and in teaching technique. Dapper in bow-tie, with thermos coffee cup ever at hand, he was to teach at Venice six classes per semester, about 36 students per class—and similar numbers for summer school and night (adult) school.

He became a teacher, in fact, specifically to work at Venice High, telling the Los Angeles Unified School District that he would accept no other job. He loved the multi-culturalism of VHS in those years—the working-class muddle of African-Americans, Asian-Americans, Latinos, Jews, whites, the smattering of Arabs, Filipinos, Pakistanis, etc.

A child of Jewish immigrants who experienced anti-Semitism as a young man, Rotman greeted every VHS student and colleague with “brother” and “sister,” as in “Good morning, Brother Achmed,” and “Good morning, Sister Washington.” He was always trying to put across the idea that all are created equal, that everyone deserves a modicum of respect. At Venice, which was marked by annual violent protests by African-American students in the late ‘60’s, this was big, important stuff.

As an English teacher, Rotman was able to impart Coleridge, Tennyson, Shakespeare et al. to students who, in some cases, could barely write complete sentences, whether due to being English learners or lack of skills. He made complex ideas in the writing accessible; put them in plain language. His reading and acting out, in clear, ringing tones, of the various parts of Shakespeare plays, brought the works to life.

The walls of room 21 were for decades marked by the names of dozens of great writers— painstakingly cut out, letter after letter, in large, ornate, formal script, by Rotman. He wanted students to be impressed when they entered his classroom, to at least get the subliminal idea that studying English Literature and Shakespeare was a grand, serious affair. It certainly was to him, a habitual reader who fell in love with words as a teenager.

As Oarsman advisor, Rotman was both hands-off and guiding. He tried to give student editors and reporters as much leeway as possible, stepping in with suggestions, not orders, and rarely imposing any editorial control beyond selecting the editor each year. He did, however, take a hand when he felt strongly about an issue, and on some occasions, even penned editorials (always approved by the staff.)

As Gondolier advisor, Rotman had a strong hand in the design of the yearbook. He razor-cut together all of the photo collages that were characteristic during his years, and was responsible for not a few gag photos.

Sometimes as much learning took place in room 21 between classes as during, with Rotman presiding. He teased out, evoked, inspired, sometimes provoked discussion and argument. This is not to say it was necessarily polite or restrained, as it often wasn’t. Impassioned was the norm. Rotman, a self-professed patriot, conservative, and Navy veteran, would debate leftist students in the late ‘60’s, and they would either join the debate, or leave the room in a huff.

Rotman adored music, from the Ink Spots, Fats Waller, Harry Belafonte to his greatest love, classical music and opera. He was fairly expert in his knowledge of the latter, and in another unorthodox bit of teaching panache, he founded the Venice High Classical Music Club, where for many years interested students sat quietly in room 21—during lunch—listening to symphonies, concertos, sonatas, arias. Rotman would hold forth about Sibelius’s Fifth (his favorite symphony), Beethoven, the great tenor, Jussi Bjorling, the cantorial singing of Richard Tucker. He was given to, on occasion, bursting into song, himself—sometimes a cantorial hymn (sung credibly), and other times, less sober utterances. For example: many were the times he would suddenly rise from his desk, coffee cup in hand (always with low-acid Kava), and boom, “Toreador-ay, don’t spit on the floor-ay! Use a cuspidor-ay, that’s-uh what it’s for-ay!”

Aaron Hirsh Rotman was born Feb. 8, 1928 on the south side of Chicago, the third son of Ada and Samuel Rotman, a Jewish immigrant from the Ukraine who gave up everything for the freedom of America. As a toddler, Aaron’s inability to say “brother,” somehow morphed into “Buddy,” and his lifelong nickname was born.

The Rotman family was too often treated as second class, as was the case with so many immigrants of the era, and these memories imprinted on young Buddy. One imagines the boy’s confusion over the cruelties of the world, the widespread anti-Semitism, and his fledgling resourcefulness. It was here that his characteristic friendliness and geniality took root. He was “always looking for a connection with everyone he met,” as his son, Mark, put it. “If a connection could be made, then communication could start, and that was the basis of friendship.” (When he retired to decidedly un-Jewish Meridian, Idaho, the man read up on the surprisingly extensive history of Jewish immigrants in the western U.S., as a sort of conversational put-you-at-ease fare for use with new friends.)

In another important imprinting experience, young Buddy was disturbed by the condescending demeanor of some of his teachers. It is not a great leap to deduce that this formed the basis of his unpretentious approach to teaching. He never talked down to students.

The Crash of ’29 also crashed the Rotman family, which lost everything, and Buddy, brothers Lionel and Willie, and baby sister Margie (who Rotman would look out for throughout her life) had to scrap. Details are sketchy, but they did manage to claw their way back, winding up owners of a candy warehouse. World War II came along, and the older Rotman brothers served in the military in non-combat roles. Bud enlisted in the Navy as soon as he was old enough, but the war was over, and he wound up with an early IBM computer group at the Pentagon.

During subsequent military downsizing, and due to flat feet, Rotman was discharged early and followed the family to L.A., where his father owned VSQ Liquors in mid-city. And things started clicking. An old Navy friend introduced Bud to one Sharlene Kahn, a recent Fairfax High graduate, and they were married in 1948. (They would remain together until her passing in 2017, an astonishing 69 years together.) Rotman went to work full-time at VSQ, earning a BA in English and teaching credential at the same time. Son Mark came along in 1950, and Donn in 1952. In 1958, he became “Mister Rotman,” joining the staff of Venice High—yet would always work two, often three jobs, to support family and a nice, modest post-war house on Everglade Street in Mar Vista.

One of those extra jobs was master carpenter—learned in the Venice High wood shop, under teacher Ed Lanning. “He couldn’t afford to hire workmen for maintenance and construction on a teacher’s salary, so he just learned it all, himself,” as his son, Mark, remembered. In time, Rotman’s handsome cabinets, desks, podiums (which graced several Venice High classrooms), came to be sought after; he always had a long waiting list of orders. Several years ago, a friend ran into a former Venice High teaching colleague, Harvey Felsen. One of the first things Felsen said was, “He was a hell of a carpenter. He redid my kitchen!”

One indicator of the man’s extraordinary impact is the fact that it is rare to meet someone who went to Venice during Rotman’s years who does not remember him. Take Maria (not her real name), a student in the mid-‘60’s, severely oppressed and abused by her mother. Not surprisingly, Maria rebelled, wound up pregnant, and dropped out of school in shame, continuing in the anonymity of adult night school. Frightened, depressed, distressed, alone, sixteen-year-old Maria found herself in Rotman’s English class—and found herself treated as if she was worth a damn. “Sister Maria, how are you this evening?” To this day, she talks about how important this was, and what a difference this man made in her life. (And she raised a good daughter, to boot.)

In 1979, Mr. Rotman was part of a Thanksgiving article in the old L.A. Herald Examiner, a kind of survey of good things still to be found in L.A.. The reporter, another former student, had visited the man in room 21 as he was packing up to go home after his last class of the day, sophomore English. Here is the end of the article.

“You know,” said Rotman, “this may sound jaded, but the ones in the city who are really thankful are the foreigners; the immigrants. I still teach night adult school English, where there are a lot of people new to the language. We had a discussion the other night—oh, it was beautiful. A Sicilian student actually stood up in class and began shouting, ‘You should-uh get down on you knees every-a-day and-uh thank-uh GOD you are in this country!”

The teacher put away his papers and closed the door.

“It was gorgeous,” he said.

A.H. Rotman is survived by his sons, Mark and Donn, of Meridian, Idaho, and four grandchildren.

Click here for his obituary in the Idaho Statesman.

Watch the full video o

Watch the full video o

![Taylor Swift’s newest album titled Midnights 🌙 takes a deeper look at the persona of Taylor herself, and according to reporter Alina Miller, although this isn’t Taylor’s best work, there are highlights worth mentioning about. 💫

Click the link in the bio to check out the full article!

[Photo Caption: Taylor Swift hits all top 10 spots on Spotify’s Billboard Top 100 chart]

#taylorswift #midnights #tiktok #antihero #spotify](https://scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.29350-15/314744727_1556543814822641_1643591421920256829_n.jpg?_nc_cat=110&ccb=1-7&_nc_sid=8ae9d6&_nc_ohc=aDxNzq2snTYAX_gAl0G&_nc_ht=scontent-iad3-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&oh=00_AfBa4EluVzZT-7d5rKyT6tLJo0UJuCvRJPSCMX71aeO38Q&oe=63965890)

Watch the full video

Watch the full video